What really happened in the children’s block of Hitler’s death camp? Did books really save Dita? Was Israel truly the land of promise and freedom in 1949? The inspiration of an international bestseller shares the truth in an exclusive interview!

Dita Kraus was ten years old when the Nazis occupied Czechoslovakia. Three years later, she and her parents were transported to the Terezin Ghetto before being sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau. During the war, Dita was one of the millions of Jews trying to survive the horrors being inflicted on them by the Nazi Regime; however, decades after the Nazi’s defeat in 1945, Dita’s story has become a nationwide bestseller, and she is known around the world as the Librarian of Auschwitz.

On February 11th, Dita Kraus welcomed three representatives of Helping Hand Coalition into her home to ask questions about her experiences during the war and her life today. Throughout the interview, Dita highlighted truth versus the inspiration written in the historical fiction novel The Librarian of Auschwitz, which was loosely based on her life, along with tales from her new memoir, A Delayed Life.

Hi Dita, thank you so much for agreeing to this interview and welcoming us into your home. Your story was first told in Antonio Iturbe’s novel The Librarian of Auschwitz, published in 2010; when did you know that he would ultimately write a novel based on your life during the Holocaust?

Ah! That was in Prague. We corresponded after he got my address through Beit Terezin, where he had inquired. He had heard that there were books in Auschwitz and he asked if they could give him more information. They told him, ‘Yes, Dita Kraus was the librarian,’ and he was amazed. He started asking questions, as you do, and we corresponded. His English was very basic and funny, and I loved it because he is a writer with imagination, so he used Spanish words and made them into English. It was amusing to read his questions, and I started to answer, which took months and months.

Then I told him, ‘Don’t write to me now. I’m going to Prague, and I don’t have a computer so I can’t answer.’ Directly, he answered, ‘You’re going to Prague? I’m going to meet you there.’ And he did come for a weekend, for two days. I took him to Terezin and around Prague. He wanted to know where I lived and where I went to school. I had to go with him around and show him. In the evening before he left, he said, ‘I think I’m going to write a book about it.’ I said, ‘Okay, okay.’ (Waves dismissively) I didn’t take it seriously, but in two years, the book was ready in Spanish. And, lately, it has become a bestseller.

You mentioned that you loved the way that Antonio Iturbe wrote his descriptions of your story. He’s a Spaniard. How did you know he would portray your life so respectfully and elegantly?

I didn’t know what he wrote because I don’t know Spanish. They sent me the book with his signature, and I had to wait. He had somebody give me a rough outline, a synopsis of the story, but this didn’t help me, and I discovered his inaccuracies only when I read the book in English, which was much later. He invented things that did not really happen the way he wrote.

Some things I had the occasion before it was published to correct him, but he, for example, gave Jewish people Czech names that are not usually Jewish. So that I prevented, and he changed them. He asked me, ‘What name do you suggest?’ So, I gave him several names. One of them was the maiden name of my mother, and this is what he used, Adler.

In the book, Iturbe writes, “A book is like a trap door that leads to a secret attic. You can open it and go inside, and your world is different.” Would you say that books saved your life during the war?

Certainly not. (laughs) They were a small section of my life in Auschwitz. A very short time. The whole thing was three-four months that I was the librarian. The books certainly didn’t save my life. Also, the imagination of an author who wasn’t there… He made quite a number of plunders. Like he describes my father, first of all, that he taught me mathematics. That he took his blanket and spread it on the floor, and we sat, and he taught me. We had a thin blanket. It was so cold; the people were freezing. He, my father, would take this blanket and put it on the mud? Or on the snow? It was… The idea is so absurd.

The Librarian of Auschwitz opens with the scene in Block 31, the children’s block, where the Nazis call everyone for a line-up, and you run towards a teacher holding a book so you could hide it. Do you remember what went through your mind at that moment?

(Confused look) No, it wasn’t like that. This was Iturbe’s version. It wasn’t like that.

What happened? You never hid the books in your dress?

No. And I had no pockets. (amused laugh)

How were the books hidden then? Did you carry them around?

We didn’t hide them. They were displayed.

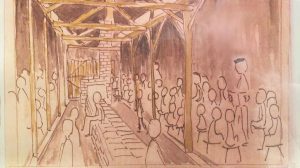

Getting up from her red leather armchair, Dita retrieved the pictures she had painted for Yad Vashem of Block 31.

She explained, “Here, this is how the block looks. Inside of the block, there is a horizontal chimney running all the length, you see? At the end, there is a chimney. By that chimney, I set up my books with another boy. Here are the books in front of me.”

And, were you running from Mengele the whole time?

I saw Mengele very frequently. We saw him frequently. He came into the block, and we saw him on the Lagerstraße, and we saw him in the hospital. We saw him. Many times, many times. He was there.

But, did Mengele ever say to you, ‘I’m watching you?’

(laughs) He didn’t look at individual prisoners. He didn’t see people.

At the end of the war, when the camps were liberated, Dita returned to Prague, the last survivor in her family. During the horrific years behind barbed wire fencing, Dita and a girl named Margit Barnai became as close as sisters, so, when everyone was released, Margit’s family offered Dita to live with them. Two years later, Dita married Otto Kraus, who had been one of the teachers in Block 31, after becoming reacquainted one afternoon. In 1949, Dita and Otto immigrated to Israel with their firstborn.

How has living in Israel, surrounded by fellow Jews, felt for you?

This is a vast question. It was a day-to-day struggle for a long time. But, since the end of the war, I was all the time aware of freedom. ‘I am free; I am free; I am free. I can do what I want.’ And that was always, always, in my mind. ‘Now, I am free.’

And, because of that, do you think the people you have met here, who were in the war, have a respect for one another? Have you found people that have gone through the same kind of situation as you?

Yes, we are a brotherhood. Anybody who says, ‘I was also in…’ Ah, immediately, there is a relationship.

Is there something about Israel that you fell in love with?

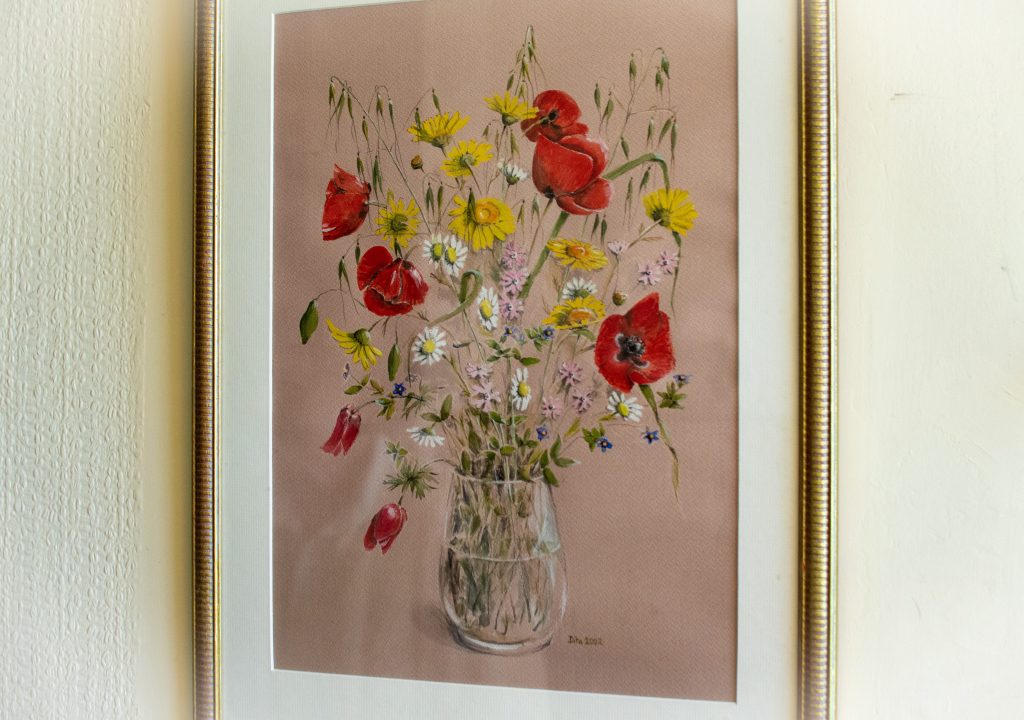

Yes, (laughs) the landscape, the Galilee, the flowers, which I paint. I have a special attitude to flowers; I feel they are somehow alive. They get attention from me, and when I paint them, I feel they are individuals.

You went from freezing cold to boiling hot.

No, we came here, we immigrated in May, and there was a chamsin (dust storm), and we were put into a tent.

And you lived in tents for how long?

Several weeks.

In what area?

At first, in Shaar Ha’aliya, under Haifa at the foot of Mount Carmel. And then, in Beit Lid, there was a HUGE tent camp where there is now Pardesiya.

How long was it until you moved to Netanya because you’ve been here for quite a while?

Ah, Netanya, we moved in 1986 when we were retired from the school.

So, you worked around Haifa then?

We were one year in a village near Netanya, seven years in the kibbutz Givat Haim, thirty years in Hadassim, and then moved to Netanya.

Did you know that you wanted to become a teacher?

I never wanted to be a teacher. I was not an inspiring teacher because it’s not in my character. I don’t have an urge to teach or to be with children. It was necessary. I had nothing else; in Hadassim, I could do nothing else. We were in Hadassim in the children’s village; there was no other job for me. I had to take this. I taught for thirty years. I was a dedicated, conscientious teacher, but I’m not sorry that it’s finished. I have no need to teach anymore.

If you’d had a choice, what would you have chosen as a profession?

Ah! (Dita said dreamily) I have; I have. That’s in my next life. In my next life, I want to see in the cellar of a museum, where they put together shards of old pottery. I love to put things together.

In 1994, your husband, Otto Kraus, published a book called The Painted Wall. A fictional telling of his time in Block 31. More than twenty years after his publication and his passing, his novel has been re-released as The Children’s Block. How do you feel about having both of your stories being read all over the world?

I still haven’t quite realized what’s happening to me now, at the end of my life. When my husband tried to get published in his lifetime, here in Israel, the same as I’m not known here and known well in the world, the same happened to him. And, I’m so sorry that he didn’t live long enough to see that he’s being recognized as a writer, as a serious literary author. He wrote several other books. Two of them about the Holocaust, and then the rest of them are novels and short stories.

How do you want us to remember your husband, or what is something he would say about his novel if he were still here with us today?

(Lovingly remembering her husband, Dita smiled as she saw Otto in her mind) He would make some funny joke. He was cynical. He made cynical remarks and jokes, usually about himself, to cover his disappointment.

Soon to become ninety years old, Dita does not plan on slowing down anytime soon. Still able to do household chores, shop, sew, drive, and adorn her walls with gorgeous paintings of flowers, Dita’s life is only getting busier after the release of her memoir, A Delayed Life, which became available on February 3rd.

What made you decide that it was time to write your story in your own words?

It wasn’t my decision. The publisher of Otto’s books in Prague, in Czechia, when we met, he asked, ‘Do you not write anything?’ I said ‘Yes, but I wrote passages, little scenes from my life, not connected, a memory here a memory there, but I wrote it in English on my computer and it’s only for my children.’ He asked if I could show it to him. When I sent it to him, he said, ‘This can be made into a book.’ So, it was his decision and his advice. And, the work done to make these passages into one whole, was done by the editor, Hana Hříbková. She did a wonderful job. She (laughs) like magic; it merged somehow. I think when you read it, you don’t find it too divided. It flows. That was her achievement.

How have your children reacted to hearing about your childhood during the war, along with the popularity you’re getting from both yours and Otto’s books?

Only my youngest son is alive. My older son died, actually, before the books were out. And, he was already too ill to care. He was ill for years. My daughter died at twenty. She died in 1971. So, she didn’t live long enough.

So, you were never able to tell them about your story of what you went through?

We were all the time until now I am friendly with those who were in the camps, those who are still alive. They visited us, and we went to visit them. Actually, they were our best friends. Several families. In Beit Yitzhak, in Mikhmoret, and in Tel Aviv. The children heard us talking. [Saying], ‘Do you remember this?’ and ‘Do you remember that?” We didn’t hide it from the children, so they knew. They heard.

Do you have a message for the younger generation who are learning about the Holocaust?

I wish they would teach their own children, when they have them, not to hate. To accept other people. Not to hate. The hatred is the cause of all the evil.

You can find Dita and Otto Kraus’ books at your local bookstore or online (Links below). Every year, new testimonies and novels are being released that share the testimonies of the people who suffered during World War II and the Holocaust. These stories need to be shared with the younger and future generations so that the world will always remember what happened and prevent the same tragedies from happening again!

Spending time with Dita Kraus and listening to her story, put into reality the hard life the survivors of the Holocaust have lived. Now, more than ever, it is time we show this group of people love, hope, peace, and joy. With only a few thousand living among us, we have the responsibility to aid those in need. Providing meals, medical equipment, eyeglasses, grocery cards, clothing, and other supplies, are just a few ways in which Helping Hand Coalition is supporting the people who paved the road for Israel to be the strong nation it is today!

While our world is in turmoil, many survivors are in need of our support. Are you able to help us continue looking after this generation of survivors and veterans? If you are, please click here to GIVE towards our mission! Your support is greatly appreciated!

Links:

Dita’s website: https://www.ditakraus.com/

The Librarian of Auschwitz: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/1118264/the-librarian-of-auschwitz/9781529104776.html

A Delayed Life: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/111/1119057/a-delayed-life/9781529106053.html

The Children’s Block: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/111/1118687/the-children-s-block/9781529105568.html

- Sitting down with Dita Kraus

- Explaining the Children’s Block layout

- Dita signing our book

- Dita showing her paintings

- Dita’s paintings can be purchased on her website

- Dita’s paintings can be purchased on her website